“Kwanqingetshe” is an isiZulu term that describes a state of stagnation. It’s something we are all familiar with; whether in our own lives when we feel we have lost direction; or – as many would feel is the situation in South Africa – living in a country where progress seems out of reach.

This is the result of the prevailing climate of a chronic lack of service delivery and a never-ending cycle of corruption within our body politic. It creates an unsettling sense that we’ve long lost direction and arrived at a place of stagnation and insecurity. Combine this with the uncertainty presented by the global pandemic, and you have the perfect recipe for ‘kwanqingetshe’.

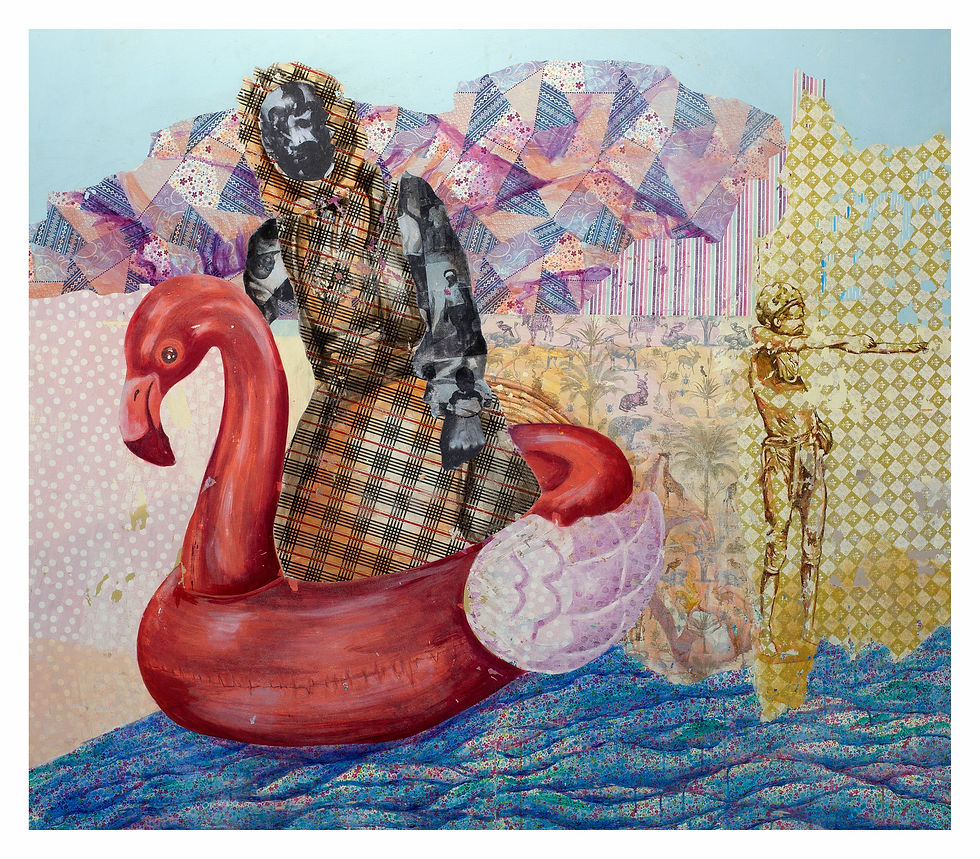

This is the subject of artist Phumulani Ntuli’s exhibition ‘A Navigation Guide to Kwanqingetshe’, which opened at the Bag Factory in Fordsburg, Johannesburg, at the weekend. It is curated by Ruzy Rusike and is the artist’s third solo exhibition. Our destination, as the title suggests, is unresolved. We exist in limbo, left only to imagine, idealise or dread the future.

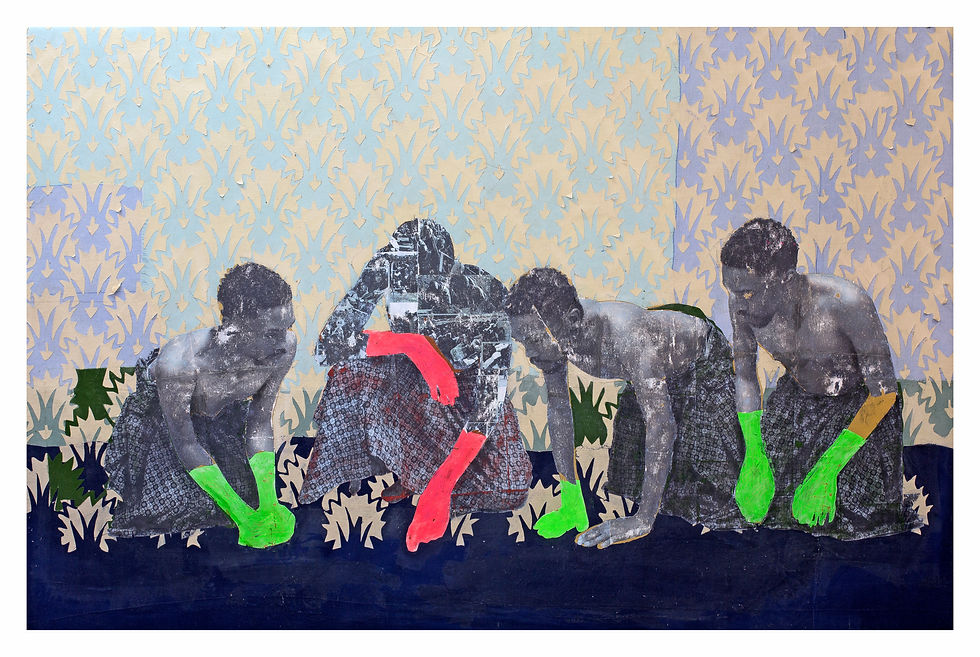

Ntuli presents a colourful body of work, consisting of mixed media collages on canvas – a mélange of paint, print fabric and archival images. In one of these works, titled ‘Stolen Songs’, we see three figures: one facing the other two, extending a clenched fist. “The gesture of extending one’s hand is about giving something, but that’s not what this figure is doing. The clenched fist symbolises a kind of pause or silencing,” Ntuli says of this work.

One of the other two figures is made partly of archival images; old pictures from the community Thuli grew up in, in White City, Soweto, in what looks like a child’s birthday party. The other figure is made partly of images from the 2012 Marikana miners’ strike and protest that was met with brute force by the South African Police Service, leaving 34 miners dead.

It’s a dark moment in South Africa that evoked comparisons to apartheid-era massacres albeit under a democratic state premised on respect for human rights.

“There’s a sense of unreliability in the narration of stories. In Marikana, for example, the narration of that story didn’t come from the miners themselves. It’s told from a different point of view. They don’t have a voice, so this figure (with a clenched fist) is someone who comes and steals people’s memories and voices.”

Born in 1986 during the four-year state of emergency imposed by the National Party government in the waning days of apartheid, Ntuli is part of a generation of South Africans who grew up at a time of both extreme violence and hope as epitomised by events such as the unbanning of the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), culminating in the 1994 election, and the death knell to a system of oppression that had seen a decades long disenfranchisement of black South Africans.

But he is also part of a generation that has seen the years since Mandela’s hope filled reign descend into the chaos of rampant corruption, unemployment, poverty and racism that keeps rearing its ugly head almost three decades since the dismantling of apartheid.

Compounding this political and social quagmire is the unease brought about by the covid-19 pandemic.

“It’s that question of (how do you) navigate the status quo? Personally, I find myself in a space of anxiety, (feeling) overwhelmed by uncertainty. Kwanqingetse is not a place, but it’s about emphasising the need to navigate to another state. We’ve been forced into this space of trying to figure it out. It can be quite situational from one individual to another, but it’s also collective. Being a black South African, specifically, having a colonial inheritance and in my personal point of view, being black man, there are also ideas of representation around masculinity, so this kind of goes into different levels. I draw from aspects of my personal life because I’m familiar with these situations,” explains Ntuli.

His first foray into art came early in life with his involvement in music at his local church. He later on developed his artistic skills, broadening his practice by using materials and found objects. On his parent’s insistence, he pursued an education in accounting through the University of South Africa (UNISA). It wasn’t until 2008 that he enrolled for his fine arts undergrad at the University of Johannesburg. “I knew I had a talent for drawing but that wasn’t enough,” he says. “I’ve always found myself in the company of artists, visiting art galleries and going to music shows, so my desire to pursue art only grew stronger.”

“My first professional practice started here at the Bag Factory with the Thupelo workshop.”

This was followed by some group shows and a project titled “Umjondolo” under the auspices of the Goethe Institute in 2012. The performance piece dealt with notions of space, city, citizenship and identity in the wake of the xenophobic attacks in the years prior as well as the subsequent forced removals of illegal occupants of flats in the Johannesburg CBD by the famous Red Ants – a private security company specialising in clearing “illegal invaders” from properties in that city.

As with ‘A Navigation Guide to Kwanqingetshe’, Ntuli’s work straddles the real and the occult in an attempt to understand reality and make sense of the past, present and possible future in the midst of this climate of uncertainty. “I feel like we are in something like a loop where certain events keep coming up. It feels like certain things have been resolved but they haven’t; like racism, for instance. It’s something we’ve dealt with for so long but it doesn’t seem to change. Likewise, the advancement of black people seems to elude our political institutions.”

.png)

Comments